Rethinking the predictors of longevity

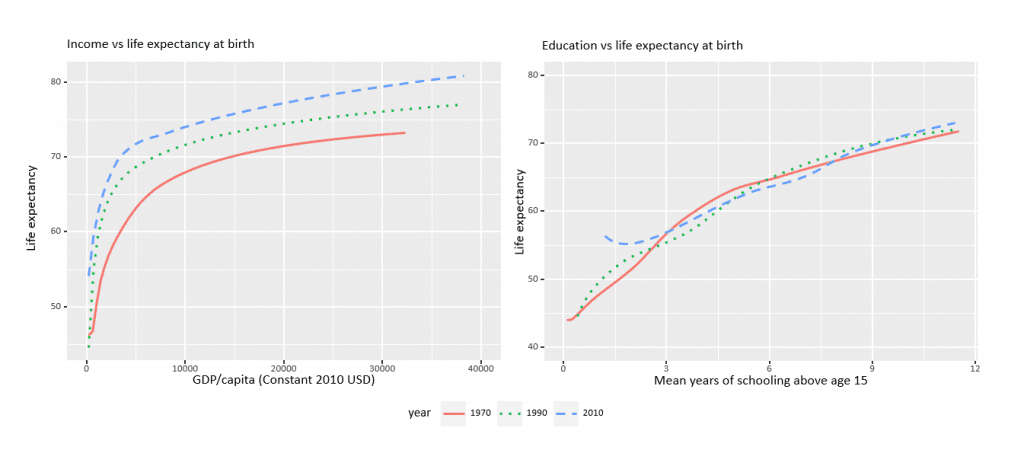

Rising income and the subsequent improved standards of living have long been thought of as the most important factors contributing to a long and healthy life. This belief has been underpinned by various theories including the widely used Preston Curve, which illustrates the upward trend in life expectancy with increasing GDP. The curves shift upwards over time, which has been explained by better healthcare. A lesser-known alternative theory however, suggests that low mortality does not come as an unplanned spin-off from economic growth but rather results primarily from higher female autonomy associated with better education.

In their study [1], the researchers tested the two opposing hypotheses and found that a person’s level of education is in fact a much better predictor of life expectancy. The team used global data from 174 countries from 1970–2015 and plotted life expectancy against the mean years of schooling of the adult population. The resulting curve is more linear, supporting their conclusion that education is a much better predictor. There is also no upward shift of the curve requiring explanation by other factors. The data was subjected to multivariate analyses to validate the findings and the same link was found when the curves considered child mortality instead of life expectancy.

Knowing whether income or education is the most important underlying determinant of increased life expectancy is important in terms of setting policy priorities in both developing and industrialized countries. While one would ideally promote both of these goals along with good health services, reality often necessitates a choice between different options. Understanding which aspect will have a bigger effect, could help policymakers decide between directing funding to programs that directly promote income growth or those that enhance school enrollment and quality of schooling.

Figure 1: Curves showing the relationship between income and life expectancy (left) and between education and life expectancy (right). [1]

The researchers point out that better education leads to improved cognition and in turn to better choices for health-related behaviors. Recent decades have seen a shift in the disease burden from infectious to chronic diseases, the latter of which are largely lifestyle-related. As time goes on, the link between education and better health choices, and therefore life expectancy, will become even more apparent.

Previous lines of research at the Wittgenstein Centre, a collaboration between IIASA, the Vienna University of Economics and Business, and the Vienna Institute of Demography of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, have emphasized the importance of improving education for poverty eradication and economic growth, as well as the ability to adapt to climate change. These findings further support the call for improved access to education.

References

[1] Lutz W, Kebede E (2018). Education and Health: Redrawing the Preston Curve. Population and Development Review 44 (2):343-361

Further information

Collaborators

- Vienna University of Economics and Business, Austria

- Wittgenstein Centre, Austria

- Vienna Institute of Demography, Austria

Related research